Were the Cartwrights involved in the Underground Railroad?

While it is certain that Reverend Joseph Cartwright purchased freedom for himself and his family, it has long been theorized that he worked in some capacity with the Underground Railroad. It is known that Thomas Smallwood and Charles Torrey worked in tandem to free enslaved people as part of the Underground Railroad, and heavily theorized that Rev. Joseph Cartwright worked alongside them. Through Charles Torrey’s memoir, it has been confirmed that he and Rev. Cartwright were in some sort of contact, but it is unclear how much. Torrey writes “I refer to Mr. Cartwright. I am going to see him soon and I shall write out his whole history for publication,” yet fails to ever mention him again (Torrey). Additionally, while enslaved, Rev. Joseph Cartwright preached at the Ebenezer Methodist Church, where Thomas Smallwood was an active member. It is thus clear that Rev. Cartwright knew Charles Torrey in some capacity and attended the same church as Thomas Smallwood. While this is highly convincing circumstantial evidence, we could not find definite proof of the involvement by Reverend Joseph Cartwright.

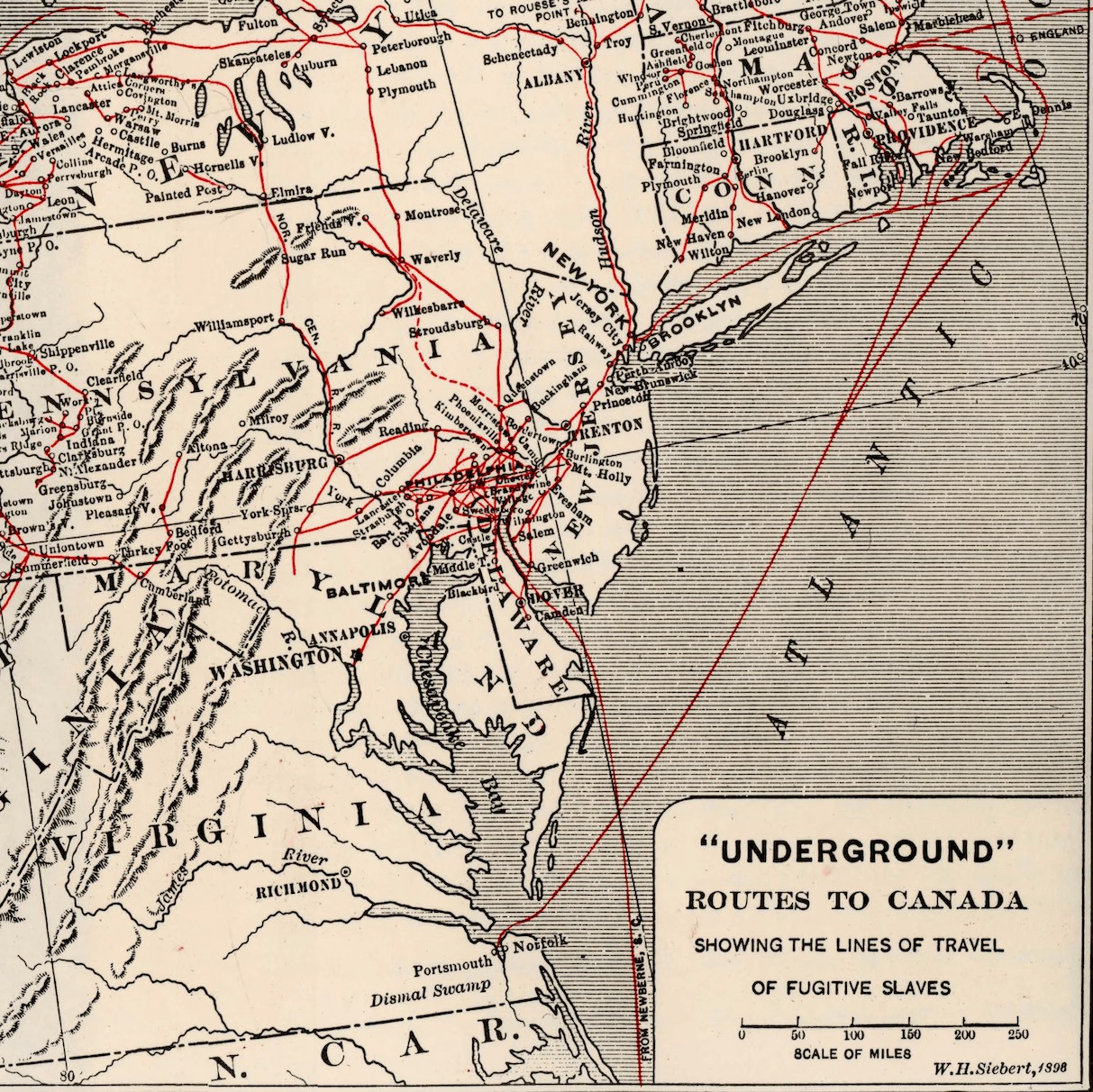

Wilbur Henry Siebert, Routes of the Underground Railroad, map from The Underground Railroad from Slavery to Freedom (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1898). Library of Congress, LCCN 68003375.

The Duckett Daughters: Emiline and Julia Ann Duckett

Under the terms of the 1824 indenture agreement between John Eversfield and Samuel Whitall, Julia Ann Duckett was meant to be manumitted on October 17, 1838. Despite this, she was kept in servitude to the Whitall family until July, 1841, nearly 33 months after she should have been freed. She was manumitted two months after her marriage to Lewis Cartwright, raising questions of if her marriage impacted her status. To this day, it remains unknown why Julia Ann was kept illegally in bondage for these additional years, a reality that highlights the fragility of legal protections for enslaved or indentured Black women. The fate of Emiline Duckett, Gracie’s other daughter, remains a mystery. She appears intermittently in the archival record, most notably in the 1829 mortgage filed by Samuel Whitall, in which she is listed as human property to be used as collateral. After this point, she vanishes from all known documentation, a fate that was not unusual for enslaved women in the early 19th century.